A few months ago, I was asked to write about the benefits of failure. For days, I considered ways to approach this writing, but nothing worked. I kept coming up empty, and the more I thought about it, the harder this topic seemed. I made up my mind to send an email and explain that I would not be able to write this post, and that I had in fact, failed at my own task.

The morning I was about to send that email, a student in my class named Max came in the room. He told me he was thinking about inspirational quotes, and he had a good one to share. “One of the steps to success is failure,” he announced. At that moment, I knew I had a way to start this blog post.

Working through a struggle is what often leads to deeper understanding, and ultimately, mastery of a topic. When we backtrack our mistakes and reverse engineer a problem, it helps us truly understand a topic and how things work.

I find that teaching is a balance of knowing when to intervene and when to stand back. It’s not always easy to identify when stepping in is necessary to help a student and when it’s better to let that student figure things out on his or her own. It’s hard to watch a child struggle with tasks, whether that task is getting the paper clip onto a stack of papers, writing a summary, or recording the steps to a long division problem. Frankly, it’s also a lot quicker to paper clip those papers myself or to say, “73!” than it is to wait.

But of course, working through a struggle is what often leads to deeper understanding, and ultimately, mastery of a topic. When we backtrack our mistakes and reverse engineer a problem, it helps us truly understand a topic and how things work. Additionally, working through something that seems insurmountable and succeeding through it develops pride, a sense of accomplishment, and strengthens confidence. Once students have “failed” at something, and figured out how to handle that failure, they are better ready to handle the later obstacles that will surely come.

An example I often use to talk about the benefits of failure is one I experienced with a small group of students last year. As they prepared to develop something to sell at their class sale for the third grade economics unit, a few students decided to capitalize on the slime craze that was all the rage at the time and sell slime to first and second graders. They found a recipe to use, developed a budget for the materials, asked for a business loan from the Head of the Lower School to pay for the materials, and placed their order. As they were ready to begin production, though, they learned that slime contained some controversial ingredients, some that had caused burns on young children’s hands.

For these three third graders, this issue was earth shattering. They knew they couldn’t sell something that might hurt anyone. They also knew they had a deadline to meet, as they had to have a product for the sale. They had already paid for supplies and used up the “loan” that was given to them. They would have nothing to sell at the sale. They were on the verge of failure.

They struggled. They looked up new recipes with cheaper ingredients that they either had at home or that we had in the classroom. These recipes didn’t work. The slime was too sticky, or too hard, or didn’t mix. Each day, one little girl from the group would come in the classroom to report on trying a new slime recipe the night before. “It didn’t work,” she would say with dejection. “Nothing works!”

My co-teacher and I wanted to intervene badly, and we did at times. “Just paint rocks instead,” we would suggest. “How about drawing a picture and making stationery? Valentine’s Day is coming!” But they were not interested in those ideas. These students wanted the slime to work.

My co-teacher and I wanted to intervene badly, and we did at times. “Just paint rocks instead,” we would suggest. “How about drawing a picture and making stationery? Valentine’s Day is coming!” But they were not interested in those ideas. These students wanted the slime to work.

After doing more research, and struggling with the need to protect their consumers, together we figured out that the finished slime itself was not dangerous. Reports came out that explained that there was a slight danger during the mixing process, but the risk of burning was not high.

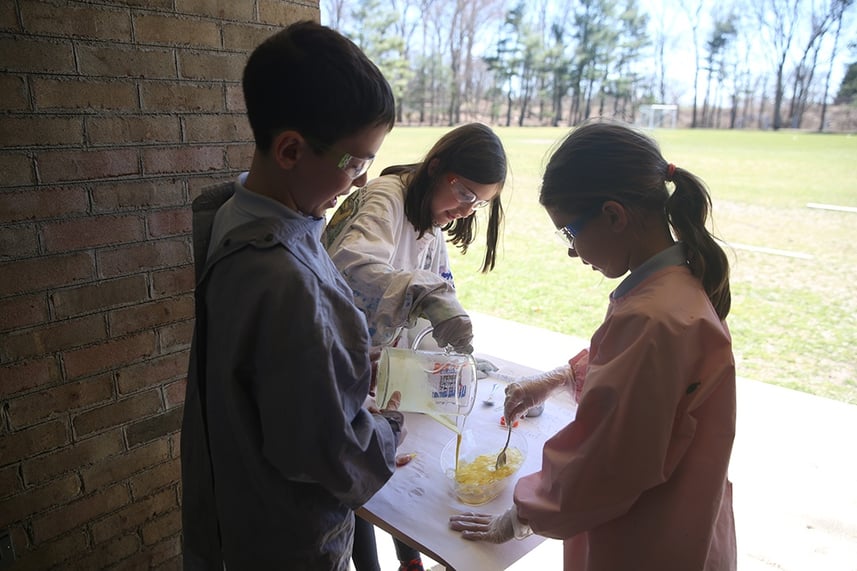

This information now presented a different opportunity — to make the slime, but this time, to think of how to take precautions. The students wore gloves, had teacher help with the “dangerous” part of the mixing, wore eye protection, and made their batches outside so they had proper ventilation. Once they figured out these issues, they went ahead and made enough brightly colored and pliable slime for the sale. They even sold out their product.

To me, going through that discomfort, failing and trying again, having recipe after recipe turn to mush, but still attempting another, and finally, figuring out a solution is one of the most valuable learning experiences I can imagine. The students made plans and saw them through. When those plans failed, they regrouped and developed a new plan of action. They persevered with a challenge and had to think flexibly. They used critical thinking skills. In the end, they felt good that something was hard to deal with, but they had been able to see it through to the end.

But those are just my thoughts as the teacher. What about the kids’ perspective?

I recently asked the students to think back on this experience, and asked what made them decide to persevere when the recipes kept failing. Why wouldn’t they just make something else when the situation became so difficult?

One student said, “I didn’t want to give up and knew we had to keep trying because I knew slime was a good product. We were selling stuff to little kids. What do little kids like? They like squishing things with their hands! Slime is perfect for that. So we just couldn’t stop. We had to make the slime work.”

Another student echoed that thought and then went a step further, saying, “I knew the slime was really cool and kids would like it, so I thought we should keep trying. Plus, I knew that if I did give up, I knew that something would always be nagging at me that I gave up on something that I knew was good. So that was what made me decide to keep trying new recipes. When the slime worked, it came out as cool as I thought, and I was happy about it. Our slime was really cool.”

In teacher speak, the kids learned about determination, resilience, and perseverance through this process of failure. They learned to believe in an idea and to see that idea through. It was hard to watch that group struggle, but it was in that struggle and those “failures” that important learning took place. Failure had its own value in deepening understanding. It was — to paraphrase Max — one of the steps to these students’ success.