If you've read Walter Isaacson's new biography on Leonardo da Vinci, then you probably made some the of the same connections that I did. In addition to being a fascinating read about a fascinating genius, the book led me to thinking in great detail about the importance of collaborative thinking as the mind interprets the world around.

Additionally, da Vinci received no formal education and this is the part that strikes me. As a result, the knowledge he acquired came solely from his own observation and curiosity.

I won't rehash the book in too much detail — spoiler alert! he paints the Mona Lisa — but some factors of da Vinci's early circumstances stood out. Isaacson is quick to point out that da Vinci was in the unique scenario of actually benefitting from being born illegitimate. Had he been legitimate, he would likely have been driven into the family business, being a notary. He would also have been traditionally educated. But because da Vinci was illegitimate, he was not qualified to join the notary guild and he had to find his own way.

Additionally, da Vinci received no formal education and this is the part that strikes me. As a result, the knowledge he acquired came solely from his own observation and curiosity. Imagine the benefits of being able to learn free of any man-made conformities. It actually sounded pretty freeing. Though this was less true during the Renaissance, compared to the ‘silo-ing’ of subjects that is the tenet of traditional learning, da Vinci had one subject and one subject only: learning.

For da Vinci, every subject was equally important and informing of the other. Each was essential if one were to unlock the limitless possibilities of human thought and creativity. Da Vinci left more than 7,200 pages of journal entries, a mere one-quarter of what he actually wrote. To compare, it far exceeds the percentage of emails and documents Isaacson was able to retrieve for his biography of Steve Jobs. Below is a paragraph from the book detailing one of those 7,200 pages:

The juxtapositions seem haphazard, and to some extent they are; we watch his mind and pen leap from an insight about mechanics, to a doodle of hair curls and water eddies, to a drawing of a face, to an ingenious contraption, to an anatomical sketch, all accompanied by mirror-script notes and musings. But the joy of these juxtapositions is that they allow us to marvel at the beauty of a universal mind as it wanders exuberantly in free-range fashion over the arts and sciences and, by doing so senses the connections in our cosmos. We can extract from his pages as he did from nature’s the patterns underlie things that at first appear disconnected.

This kind of approach to interdisciplinary learning is not unique to da Vinci. Actually, it is ancient. The Greeks categorized music under the umbrella of a single tri-disciplinary subject that included math and astronomy. This left me with the thought, “Are we all selling ourselves short?” Might we all be capable of the same multi-dicisiplinary expertise and could it be that the enforcement of choosing a career is actually a limitation to our possible contributions to the world?

If da Vinci were alive today, he’d likely be unemployed. As mentioned, he had no formal education, no degree in any field yet he is credited with being an expert artist, musician, engineer, inventor, architect, scientist, you name it. We often think of him as a painter but his employment at the court in Milan was for his ability to invent, play and improvise singing and playing musical instruments (though he tried to market himself as a military tactician!).

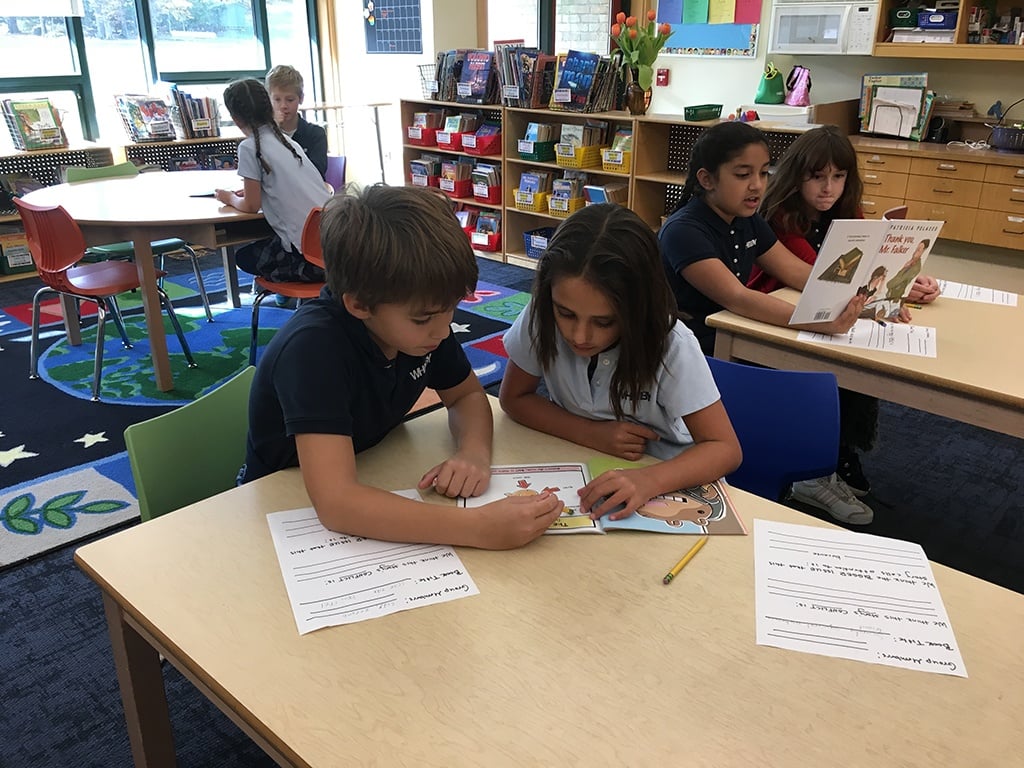

I think da Vinci would approve of how Whitby promotes inquiry, curiosity, and exploration. In his tradition, we encourage our students to observe, take apart, and connect their thinking across disciplines.